Have you ever wondered how it would be if we, as programmers, coded in the same way? If we created code using a similar set of universal rules as in the case of the language we speak and write in? What if there were no major differences in the developers’ coding?

Well… I thought about it, but I don’t think that could be possible, because programming languages are evolving faster than we think, faster than we do. They evolve and maybe sometimes they surpass us. Which, if you think about it, is quite normal, right?

And there are still other reasons for this Babel-like mixture of styles. First, the percentage of developers that haven’t yet reached the mastery level is significantly higher than of those who have. And when you’re a beginner, you don’t know all the rules. You don’t think of the rules, there’s so much more to focus on anyway.

Continuous learning from different sources can also create the premise for the existence of different styles of writing code. Not to mention the personal preferences or even the ego (even though the last one should not exist at all).

But how can we put a little bit of structure in this complex diversity? Simple! By creating it. 🙂 To be more specific, by creating some standards and principles that we can take into consideration when we write code.

These standards are designed to make our lives easier. To avoid spending a lot of time understanding our colleagues’ code, or worse than that, refactoring it.

Coding principles

The most important principles you should take into consideration when you code, whether you’re a frontend or a backend developer, are:

DRY (Don’t repeat yourself) – This is probably the single most fundamental rule in programming – avoiding repetition. Many programming constructs exist just for that purpose (e.g. loops, functions, classes, and more).

KISS (Keep it simple, stupid!) – Simplicity (avoiding complexity) should always be a key goal. Simple code takes less time to write, has fewer bugs, and is easier to modify.

YAGNI (You aren’t going to need it) – You should try to not add functionality until you need it. Extreme programing co-founder Ron Jeffries wrote: “Always implement things when you actually need them, never when you just foresee that you need them.”

Open/Closed Principle – Software entities (classes, modules, functions, etc.) should be open for extension, but closed for modification. In other words, don’t write classes that people can modify, write classes that people can extend.

Minimize Coupling – Any section of code (code block, function, class, etc) should minimize the dependencies on other areas of code. This is achieved by using shared variables as rarely as possible.

Code Reuse is Good – Reusing code improves code reliability and decreases development time.

These are all basic and general rules every developer should take into account. Yet, not all of them do. What I’m going to present next are the main mistakes I’ve come across in my four years of experience as a frontend developer, mainly in coding CSS.

1. Overspecificity

The main problem with bad CSS is that it generates more bad CSS.

For sure you’ve met the situation when you probably needed to fix a CSS bug and found a selector using ids or some inline styles and had to resort to !important. These examples have one thing in common: overspecificity.

Specificity in CSS is how specific you are when you define your CSS declarations.

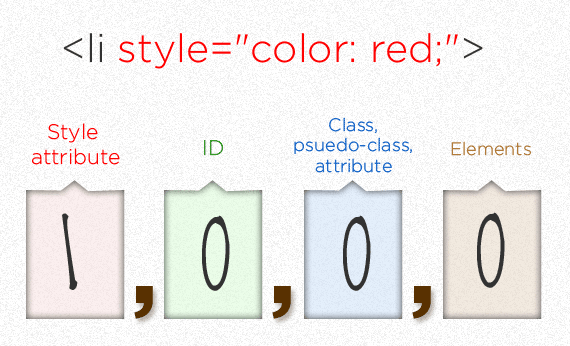

Ever wondered how to calculate the specificity? For a better understanding, here’s an example:

The above images highlight the fact that on the < li > element we may have a specificity value of 1000, which means that the red color will be applied only on this element, or it can be 1 in case we would like to keep the same style for all < li > elements.

Here is an example of unlucky selected element:

#layout #header #title .logo a { display: block} |

If you read this selector from left to right, you should recognize the structure: layout area -> header -> title -> logo -> link. And for those of you who (have to) write this, you should also admit that this is very (i.e. too) specific.

Overspecificity makes your CSS less maintainable and readable.

2. Using ids

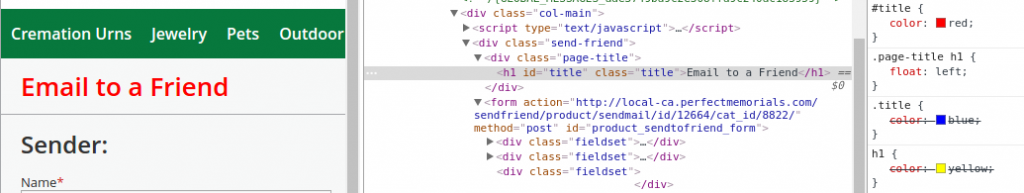

#title {color: red;}.title {color: red;}h1 {color: red;} |

Which one will you choose? I hope it’s the last one.

The id element is unique, it’s not re-usable on that page. This is the beginning of a downwards spiral into overspecificity. Ids are meant for singletons. There are times when someone intentionally wants something to be used only once on a page. Id selectors would be useful for that purpose since they would signify once per page.

In the image below you can see how an id selector can re-write any other element style. The id specificity value is 100, the class one is 10 and the tag is 1.

3. Long selectors

Another mistake which increases the overspecificity is long selectors.

#header #title .left-side img.logo { opacity: 0.5; } |

If you use this kind of selectors (that are more than three levels deep), you’re increasing the specificity. For the example above, you can keep just .logo. In general, your selectors should be only two levels deep, or three at the most.

4. Inline style

I think that the inline style is the nightmare of the frontend developers, and also violates the reason we use CSS: to separate style from structure. We stopped mixing the styles with HTML in the moment we stopped using tables for layout. From a specificity perspective, an inline style can only be overridden by an !important flag.

5. Not Using a Proper CSS Reset

The browsers provide default styling for HTML elements. There has to be a fallback mechanism for people who choose not to use CSS. Anyway, there is rarely a case of two browsers providing identical default styling, so the only real way to make sure your styles are effective is to use a CSS reset.

Once you include a CSS reset effectively, you can style all the elements on your page as if they were all the same to start with.

* { margin:0; padding:0; } |

The above example is not a full reset. You also need to reset, for example, borders, underlines, and colors of elements like links so that you don’t run into unexpected inconsistencies between web browsers.

6. Not Using Shorthand Properties

#selector { margin-top: 50px; margin-right: 0; margin-bottom: 50px; margin-left 0;} |

There are a lot of lines, right?

Fortunately, there is a solution, and that’s using CSS shorthand properties. The following section of code has the same effect as the above, but we’ve reduced our code by three lines.

#selector { margin: 50px 0;} |

You can also use shorthand properties on declaring fonts, backgrounds and so on.

7. Using 0px instead of 0

#selector { margin: 20px 0; } |

instead of

#selector { margin: 20px 0px; } |

An easy way to save bites in CSS files is to not include units when a value is 0. When you’re working with a huge file, removing all those superfluous px can reduce the size of your file.

0 = 0px = 0in = 0pt = 0cm = 0em = 0% and so on. Since they are all equal, it doesn’t matter which you use and so many people use the shortest one since that means less typing.

Moreover, if there’s one thing all browsers calculate identically, then it’s the value of 0. Every browser understands the meaning of zero.

8. Not Providing Fallback Fonts

In a perfect environment, every computer would always have every font you would want to use. Unfortunately, we don’t live in this type of environment. But, you can still use fonts like Helvetica that aren’t necessarily installed on every computer.

Font stacks are a way for developers to provide fallback fonts for the browser to display if the user doesn’t have the preferred font installed.

#selector { font-family: Helvetica, Arial, sans-serif;} |

9. Using Only One Stylesheet for Everything

This is one of the biggest don’ts when it comes to structuring your code. Because if you want the websites you work on to be easily maintained and to have a healthy modularity, you need to split the stylesheets into a few different files. For example, you’ll have one for a CSS reset, one for IE-specific fixes, and so on.

Moreover, this approach would make your life way easier when you’ll have to change something in the code. (Not to mention that whoever might come work after you on the same project would be forever grateful to you as he/she won’t have to spend half of the development time digging through your dirt).

Maybe you prefer to squeeze them all in one file, and that’s okay. But if you have a hard time maintaining a single file, try splitting your CSS up.

10. Redundancy/DRY

Redundancy means you have a tendency to repeat yourself in CSS. It’s pretty obvious that if you repeat yourself, you waste time, so DRY (don’t repeat yourself).

.some-title { font-weight: bold; }.some-other-title { font-weight: bold; color: red } |

We can write this like:

.some-title, .some-other-title { font-weight: bold; }.some-other-title { color: red; } |

It is also important to comment your code, as the comment code is a “mirror image” of itself.

Well… these are just some of the many mistakes that we can make. Avoiding them is part of the learning process and I hope I’ve opened or contributed to your “do not” list.

They say the way we write reflects our thoughts. If things are set and clear in our head, it will reflect in the code, thus avoiding a continuous refactoring process. If you’re not there yet, don’t worry, the storm will calm down in time, with experience. Evolving is both natural and necessary. And whenever you make mistakes, all you have to do is fix them. 🙂

Article written by Madalina Gradinaru